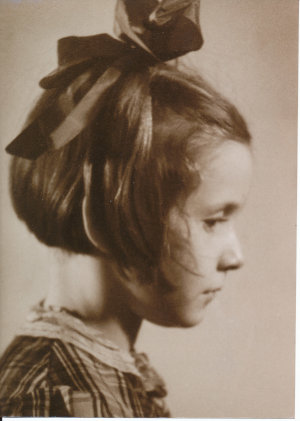

As a 9-year-old in a German concentration camp in 1943, Marion Blumenthal Lazan had none of the staples children normally took for granted, like paper, pencils, books or games. But she took comfort in her active imagination and four perfect pebbles.

Life in Bergen-Belsen was terribly bleak, with not a tree, flower or blade of grass in sight. Starvation, disease and death were her daily companions.

To keep despair at bay Marion created imaginary games. She decided that finding four pebbles of about the same size and shape would mean the four members of her family would all survive – her parents Walter and Ruth, her brother Albert, and she.

The game provided relief because she always came out a winner. “I always found my four pebbles. I made it my business to find them. I cheated all the time. When I found them, I put them in a safe place,” she admitted to an Atlanta audience during Intown Jewish Academy’s Holocaust Remembrance Series.

“This game gave me something to hold onto, some distant hope.”

Hope barely breathed in Bergen-Belsen, where approximately 50,000 people died at the hands of the Nazis – mostly Jews, including the young diarist Anne Frank. Overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and a lack of adequate food, water and shelter led to typhus, tuberculosis, dysentery and other disease outbreaks. "As children we saw things that no one, no matter what age, should ever have to see."

Lazan existed on a slice of bread and hot watery soup with grisly meat and turnip and potato peels every day. “Bread was later given to us just once a week, and only if our so-called quarters were neat and in order. Our birthday present to one another was that little piece of bread we had saved up from the previous week.”

A Narrow Escape

One day promised heartier fare. Her mother had smuggled potatoes and salt out of the kitchen where she worked. She proceeded to cook soup in secret on the bunk she shared with Marion. All of a sudden, German guards entered for a surprise inspection.

As Lazan relates: “I was on the bunk with my mother trying to hide and shield what she was doing. Soup was simmering, just about finished. In our rush to hide that setup, the boiling soup spilled on my leg. We had been taught self-discipline and self-control the hard way. I knew if I cried out it would cost us our lives.”

Their dark, crowded barrack resulted in other perils. It often led inmates to trip and fall over dead bodies. “As children we saw things that no one, no matter what age, should ever have to see,” Lazan says.

Fueling the Fire for a Holocaust

The stage was set in 1935 when Nazi Germany enacted the Nuremberg Laws, thereby providing a legal framework for the systematic persecution of Jews. They stripped Jews of citizenship, barred marriage and relations between Jews and other Germans, prohibited Jews from flying the German flag, and more.

The vise was tightening for families like the Blumenthals, who lived above their shoe store. “It was then that my parents decided to make arrangements to leave the country,” says Lazan.

“My grandparents, who were in their late 70s and ill, refused to leave their home. They could not see the urgency. My grandparents passed away in 1938, within just 11 days of each other. Soon thereafter we received our papers for immigration to America.”

On Nov. 9, 1938, Nazis ransacked the family apartment during Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, when Germans unleashed pogroms on Jews across the country.

They seized Lazan’s father, taking him to the German concentration camp Buchenwald. Miraculously, they released him three weeks later because the family’s papers were in order to emigrate to America.

My parents were assigned to take care of some 125 children.

“We were forced to sell both our home and our business for a fraction of their worth. In January 1939 we left for Holland, from where we were to sail for the United States,” says Lazan. “For almost nine months, while awaiting our quota number from the American State Department, my parents were assigned to take care of some 125 children. They had been sent by their parents from various parts of Europe to escape from the Nazis.”

Connection with Anne Frank

Lazan claims Anne Frank as a kindred spirit, although the two girls never met. Both born in Germany, they also lived in Holland. “Mine is a story Anne Frank might have told had she survived. It is also a story with a message of perseverance, determination, faith and above all, hope.”

In December 1939, Lazan’s family was deported to the detention camp of Westerbork in Holland to await their voyage to America. In May 1940 – just one month before the planned departure – the Germans invaded Holland. The family couldn’t escape, and their belongings perished as Germans bombed Rotterdam’s harbor.

‘The Boulevard of Miseries’

Unfortunately, now they were awaiting deportation to a concentration camp. Finally the Tuesday came in January 1944 when they had to march down a railroad platform known as the “Boulevard des Misères,” or Boulevard of Miseries. When they saw the cattle cars to board, the family feared the worst.

“I remember it was a bitter cold, pitch black, rainy night when we arrived at our destination, concentration camp Bergen-Belsen in Germany. We were pulled and dragged out of the cattle cars and greeted by the German guards who were shouting at us and threatening us with their weapons and with the most vicious attack dogs by their sides. I was a very frightened 9-year-old, and to this day I still feel fear whenever I see a German shepherd.”

“Of the total 120,000 men, women and children that departed Westerbork,” Lazan adds, “102,000 were doomed never to return.”

The miseries of captivity in Bergen-Belsen included frostbite from roll-calls at times lasting from early morning until late at night without food, water or protective clothing.

Wolves Seek Sheep’s Clothing

The population was dying off rapidly, but not nearly fast enough to satisfy the Nazis, according to Lazan. “It was decided to send three trainloads of our people to Eastern Europe, to the extermination camps and the gas chambers. After 14 days of this surreal and horrifying journey, the German guards stormed frantically through the train seeking civilian clothing so they would not be recognized by the allies. We knew then the war was coming to an end. The Russian army liberated our train and led us to a nearby farm village in Eastern Germany.”

By then Lazan was 10½ years old and weighed 35 pounds, or 16 kilos. All four family members were ill with typhus, and her father died from it just weeks after liberation – after surviving 6 1/2 years in refugee, transit and concentration camps.

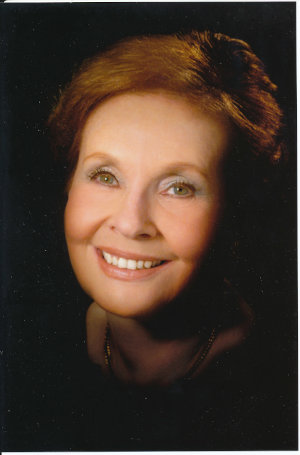

The children and their mother gradually recuperated and started life anew in America on the eve of Passover 1948. Two months after high school graduation in Peoria, Illinois, Marion married Nathaniel Lazan, whom she had met in synagogue on Yom Kippur. He later became an Air Force pilot. They celebrated their 68th anniversary in August 2021 with three adult children, nine grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

The Ripple Effect of Pebbles

Marion’s memoir, Four Perfect Pebbles, has been translated into German, Dutch, Hebrew, French and Japanese. She is grateful the story will live on for future generations. Although she has spoken to 1.5 million students and adults over these past 20 years, the effort always drains her.

But she reasons, “Today’s generation will be the very last that will hear these stories firsthand. When we are not here any longer, today’s youth will have to bear witness. As difficult as it is, the horror of the Shoah must be taught. Only then can we guard it from ever happening again.

“Each of us must do everything in our power to prevent such hatred, destruction and terror from recurring. We can begin by having love, respect, tolerance and compassion towards one another, regardless of the religious belief, regardless of the color of our skin, regardless of the national origin. This respect toward one another must begin in our homes.”

[Published on Aish.com, November 7, 2021]