The day after she arrived from Vienna, seven-year-old Rella Hudes flashed a big smile for the camera as she sat on her new tricycle in the garden of her new home in Sheffield, England. It was the worst time of her life.

She had just escaped Austria through the Kindertransport (Children’s Transport), a rescue effort that brought thousands of refugee Jewish children from Nazi-occupied territories to Great Britain between 1938 and 1940. They fled to safety with a new family, a new country, and a new life.

Rella left behind her Orthodox Jewish family and her native Vienna to start a new life with Philip and Lilian Adams, an elderly Christian couple in Sheffield who had volunteered to sponsor a Jewish child. They offered her a china doll and more toys than she could imagine. Still, she cried all the time.

England,on the day after her arrival from

Vienna in 1939.

“I felt completely abandoned. The food, the language, everything was so different. All I did was cry,” recalls 84-year-old Rella Hudes Adler in a telephone interview from her home in Florida. “I looked up at tea time when I was eating and everyone around the table was all crying. They just empathized with how I was feeling and they couldn’t do anything about it.”

A new book by Jason Hensley, “Part of the Family: Christadelphians, the Kindertransport, and Rescue from the Holocaust,” features her story as a child survivor. The Adamses were Christadelphians, a small international Christian group.

“I lived a strictly Christian life. But I knew I was Jewish because of the contact with my aunt in America. It was a decision of mine to continue becoming Jewish.”

During the eight years the couple sheltered Rella, they taught her Christian beliefs and took her to meetings and Sunday school. “I lived a strictly Christian life. I knew it backwards and forwards. But I knew I was Jewish because of the contact with my aunt in America. It was a decision of mine to continue becoming Jewish. I had no role models,” she says, explaining she didn’t see another Jew again until age 15.

As Rella recalls, the Christadelphians were pro-Jewish and encouraged her to keep in touch with what family she could, writing to her aunt in the United States and her uncle in Palestine. Since Britain was at war with the Nazis, she couldn’t communicate with her mother in Austria.

That left her mother, Klara, to care for her and an older brother, Siegmund. Their life in Vienna grew ever more frightful. “When Germany marched into Vienna, from one morning to the next, it was awful. We had to move from our apartment to a different place.”Her father, Isak Hudes, worked as a cabinetmaker in Vienna until emigrating illegally to Palestine in 1933. He remained there with relatives until his death from natural causes in 1942. Rella reasons that he couldn’t take his wife and young children, including a toddler, with him.

Rella remembers going to a Jewish school that became a target for The Hitler Youth, the youth organization of the Nazi party. “I stopped going to school because they would pelt us with rocks. I had a lot of trouble with The Hitler Youth. If I went from my grandmother’s to a store to buy something, they came and roughed me up and took my change. When we moved to a Jewish neighborhood they came and tied me to a lamppost with my arms behind my back. My brother came to find me. My family wouldn’t let me out after that.”

Somehow, her mother managed to save her through the Kindertransport. The train and boat rides to England were a happy time for Rella because she saw children again after having had no playmates for at least a year when she didn’t go to school. Only after the other children went their different ways and left her alone at the train station in England did she became upset. Nobody around spoke German. As she puts it, “I lost my language and I never spoke it again.”

“I felt abandoned and alone. It was the worst time of my life.”

A lifetime later she easily recalls what it felt like to have her world turn into upside down. “I went through cancer, surgeries in my life,” the senior citizen says. “But nothing was as traumatic as the transition from Vienna to Sheffield. I felt abandoned and alone. It was the worst time of my life.”

The abandonment went deeper than Rella knew at the time. She would later learn that her mother, brother, grandmother and aunt had perished in the Nazi death camps.

Meanwhile, the Christian couple who took her in gave her a good life in England. She enjoyed a comfortable childhood, filled with friends, dogs, toys and sports. They made sure she corresponded regularly with her Aunt Ida (father’s sister) in the United States and Uncle Shlomo (mother’s brother) in Palestine.

With crucial assistance from Jewish agencies in England, Aunt Ida managed to secure an American quota for her brother’s only living child. “It was a real saga, of which I knew nothing,” says Rella.

Leaving England to live with Aunt Ida in the quasi-shtetl of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, at age 15 demanded a whole new level of adjustment. The only thing that was familiar, besides her favorite aunt, was the English language. “I was a Jew through and through, how I felt and who I was. But when it came to observing all the holidays and all the rituals, I felt like a complete outsider.”

Her aunt took her to see the Lubavitcher Rebbe, because Rella wanted to continue to read the King James version of the Bible she knew so well from her time with the Christadelphians. Although her aunt wanted to enroll Rella in an Orthodox seminary, the Rebbe instead suggested having three religious girls her age take her under their wing.

“Thank you from the bottom of my heart. You made it possible for me to have a life, and children and grandchildren.”

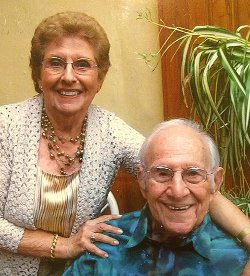

All of the helpers along the way made Rella who she is today: a wife who just celebrated 62 years of marriage with her husband, Harold; mother of three, and grandmother of four. “I am this person who had no family of her own, except an aunt. I instilled in them that family is very, very important.”

If the Christadelphian couple were alive today, she would tell them: “Thank you from the bottom of my heart. You made it possible for me to have a life, and children and grandchildren. I will be eternally grateful for that and so will my children. You really did a mitzvah.”

[Published on Aish.com, July 30, 2016]