On April 24, 1941, a tiny boy was born in a giant cave near Kiev. His parents named him Grischa. “You were born at a very inopportune time,” his mother, Manya, would later tell him.

Manya and her husband, Tolek Grinblat, had been resistance fighters against the German army. Tolek was from Lublin, Poland, and in 1939 joined other young people from his Jewish ghetto in blowing up Nazi convoys and protecting the synagogue. When Schutzstaffel (SS) soldiers came looking for him, Tolek fled toward the east. He met Manya in the Ukrainian resort town of Kremenchuk.

Soon after marrying in 1940, they heard frightening reports of Jews being targeted for extermination by special killing squads that followed the German army as it swept across Europe. The young couple ran for their lives, eventually taking refuge in an underground cave system in the Ukraine with a ready supply of fresh water.

Dozens of other people also were hiding in the cold, damp caves there. They slept in the dark interior during the day and left at nightfall to forage for food in nearby fields and farms. Upon their return, they always slipped back into the cave feet first. They had to say the right code word to enter, otherwise the cave guards would attack them.

One time upon leaving the cave to find food, Manya and Tolek were caught in a firefight between Germans and Russians. Shrapnel hit Manya in the leg. Her husband knew she must receive medical attention or die. In desperation, he left baby Grischa in the cave with fellow Jews while he sought care for his beloved wife, according to “My Parents’ Unwavering Will: The Story of Hershel Greenblat” (William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum, Atlanta, GA, 2016).

Nearly two months later when the couple returned to the cave, they were relieved to find their baby safe. Eventually Manya would require more medical attention. The family left the cave for good and moved further east, where Manya was hospitalized for several months. Her resourceful husband found work in a bakery. However, in his desperation for food for his family, Tolek stole some bread and landed in a Russian prison for 2 ½ years. During that time Manya – a 4’11” Yiddishe mama who was strong and determined – worked as a seamstress to provide for Grischa and his new sister.

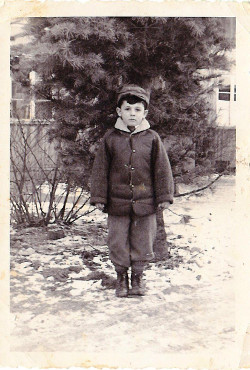

September 1945, one week after Hershel's father was released from a Russian prison

father was released from a Russian prison.

After reuniting, the Grinblats boarded a cattle car on a train bound for the American-controlled zone in Austria at the end of World War II. The family spent five years in two displaced persons (DP) camps run by the U.S. Army. Again they shared close quarters with other refugees – just as they had in the caves for the first year of Grischa’s life. Even so, their lives began to blossom. Hundreds of children enjoyed playing together in the DP camps. Adults recreated their lives as bakers, cantors and shopkeepers.

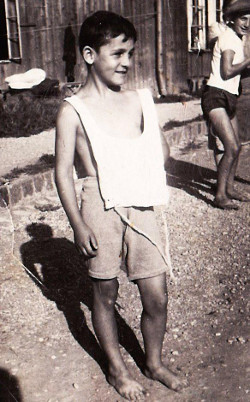

Grischa outside the barracks at one of the DP camps in Austria

of the DP camps in Austria

With his brood safe, Tolek set out by bicycle for different DP camps. He longed to find any news about other family members. He discovered that his entire family, including 15 sisters, had died in the gas chambers of Majdanek, a concentration camp on the outskirts of Lublin. Manya’s parents, brothers and families had perished at Babi Yar, a ravine near Kiev where an estimated 100,000 Jews, gypsies, Communists and Soviet prisoners of war were massacred. Two sisters made it to Israel.

At long last, the Grinblats were blessed by opportune times. In 1950 they packed up their Shabbat candlesticks and family pictures and sailed to America to begin a new life.

“My father woke me up early,” Grischa, now known as Hershel, recalls with tears. “He said he needed to take me up on deck. There was something he wanted me to see. Very beautifully lit up, in all her glory, was the Statue of Liberty.

“That was the only time my father held my hand. He was a disciplinarian, an excellent father, but very reserved. It was the first time I saw him cry.”

The parents, who by then had three children, began their new life with $80 and new names. Grischa became Hershel. Grinblat became Greenblat. Sponsored by the Atlanta Jewish Federation, the family took a train South and never looked back.

With a $1,800 loan, Tolek – or Abraham – bought a small grocery store in an Atlanta ghetto called Buttermilk Bottom. Compassionate due to his experiences during the war, he sold food on credit to customers who’d say, “Just put it in the book.” He gave food to people who could not afford to pay at all. His wife sent chicken soup to the sick. The goodwill gestures attracted the attention of a local minister, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He came into Abe’s Market to introduce himself to the owner and they soon became friends.

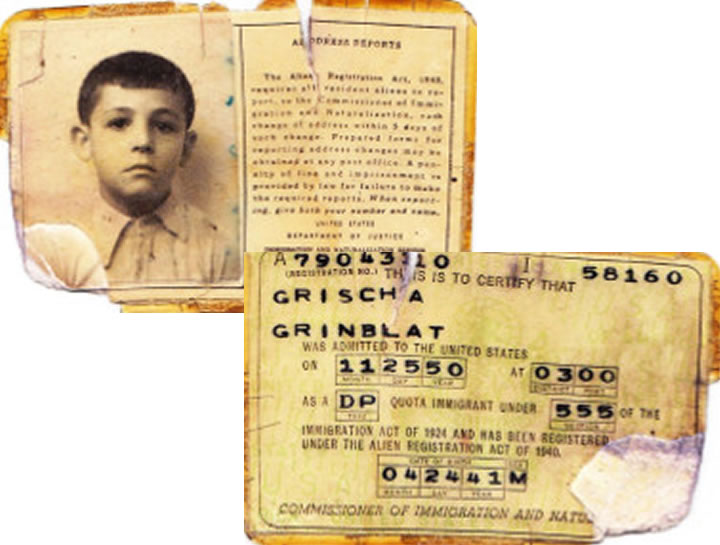

The green card Grischa carried until he became Hershel, a U.S. citizen

Meanwhile, Hershel started elementary school not knowing a word of English. More than 65 years later, the date remains etched in his memory. On Dec. 12, 1950, he walked into the school with the Orthodox woman who sponsored his family and met a teacher who would change his life.

“She had that air about her,” he recalls of Frances Zaglin. “She took me by the hand and spoke Yiddish to me. She told me, ‘No more Yiddish, no more German, no more Polish. You’re going to be an American.’ ”

Mrs. Zaglin sat with him after class, patiently teaching him the English alphabet and reading. Like his parents, Hershel possessed great tenacity. He gobbled up short library books on U.S. presidents, which fed his love of history. His teacher’s kindness went beyond the classroom. She accompanied Hershel downtown to help his mother pick out his first pair of jeans.

“My clothes were old. They were the clothes I wore in DP camps. She would not let me be bullied by third-graders for being different. Mrs. Zaglin took me by the hand and put me on the path to becoming an American,” says a grateful Hershel, now retired after a career in the furniture business.

A husband, father of two and grandfather of five, he pays it forward by educating thousands of youths every year about the Holocaust. “They’re the last generation that’s going to be able to listen to us. As long as we can speak we’ll do it. We don’t want the world to forget what happened.”

Frances Zaglin, 90, kvells to hear about her former pupil teaching young people, Jews and gentiles alike. “I cannot express how thrilled I am about what he is doing with his life,” she declares. “Living in a cave. Then coming to a sweet neighborhood with a lot of Jews. He just adjusted beautifully.”

[Published on Aish.com, April 30, 2016]