Sam Weinreich is urgently telling his story in his living room in Memphis, Tennessee. It’s the story he’s told many times over the years and he doesn’t want to skip any details.

Weinreich, 100, and his wife, Frieda, 95, are the oldest Holocaust survivors living in Memphis. He suffered under the Nazi regime for almost six years and wants the world to know what that was like.

“People who went through almost the same exact thing, they’re not here any more,” he told Aish.com before he reached the century mark this summer. The memories of his time in concentration camps and his liberation still remain vivid.

More than 50 children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and family members flocked to Memphis to celebrate Weinreich’s 100th birthday. Thanks to the family's social media campaign, their patriarch received more than 2,000 birthday cards from Alaska to Australia and Paris to Peru.

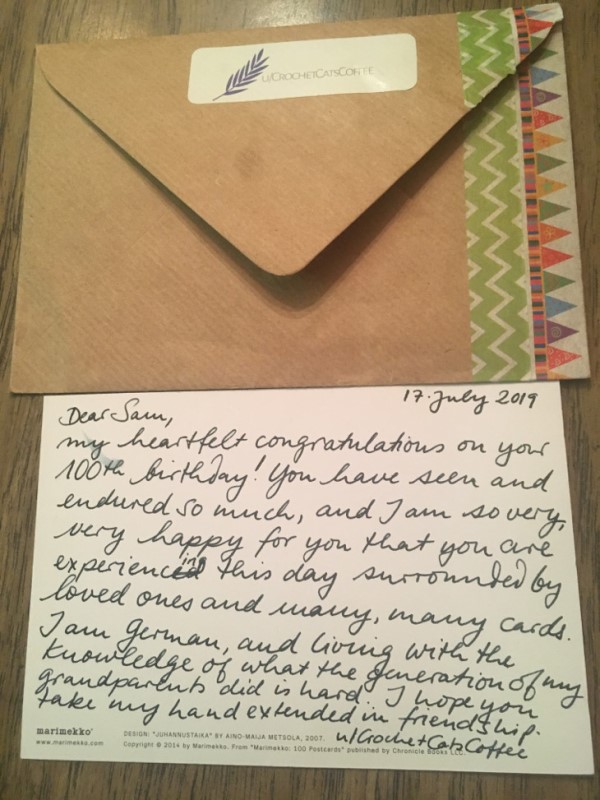

A card from Germany holds a place of honor on Frieda Weinreich’s walker. “Dear Sam,” the stranger wrote, “My heartfelt congratulations on your 100th birthday! You have seen and endured so much, and I am so very, very happy for you that you are experiencing this day surrounded by loved ones and many, many cards. I am German, and living with the knowledge of what the generation of my grandparents did is hard. I hope you take my hand extended in friendship.”

Born Sept. 3, 1919 in Lodz, Poland, Weinreich grew up with four brothers and four sisters. The family owned a total of four antique and furniture stores and lived comfortably. Following local custom, the children went to public school from ages 7 through 14, then learned a trade. Furniture finishing became Sam’s calling. He worked for a brother who had a shop on the street where they lived.

Music Wove a Backdrop for His Life

Weinreich also had a talent for music that was apparent early on. He began singing in the school choir at age 8. Still a synagogue choir member at age 100, he was polishing his solos for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

Growing up in Poland he was a passionate member of a Zionist youth organization. Weinreich and other young idealists longed to build a Jewish state one day. But Adolf Hitler replaced their innocent dreams with the nightmares.

It all hit home as Weinreich approached his 20th birthday. “We heard rumors that Hitler had taken over Austria, Romania and Czechoslovakia,” he recalls. “People came in the store and said to my father, ‘Mr. Weinreich, save yourself. You know what Hitler will do to you all.’ My father said, ‘Where will I go? We don’t have any place to go.’ “

Sept. 1, 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. Within a matter of days, the Germans attacked Lodz, which formed the second largest Jewish community in prewar Poland, after Warsaw.

“I was enlisted to be a fireman at night. The Germans bombed the few planes Poland had,” says Weinreich. “On September 1, a guy knocked on the front door where I had duty. ‘Please wake up everybody. All the young people: Take yourself and go to the capital.’ We put up a stand against the Germans. I sounded the alarm. I didn’t know what to do. I woke up my family. …

“My father said, ‘Listen, I am of age now. I’m not going. You’re a young person. You obey whatever the Polish government says.’ My brother Hershel, two years younger, and I put on our best clothes. We walked, finally dusk came. In the daytime, planes came out from the sky. With machine guns they were mowing down people. The roads were full of people, unbelievable. Horses with wagons. Everyone was running toward the capital.”

Moving at night, picking fruit and carrots in fields to feed themselves, the two brothers made their way to their grandfather’s in Warsaw. Food was scarce.

Their grandfather heard the news that life in Lodz had returned to normal. The Germans had made people reopen their stores, and soldiers were walking in the street singing. He urged his two grandsons to return to Lodz.

For a while life remained peaceful. Then the Nazis began enacting laws against Jews. “They made us wear yellow stars. You could not walk out in the streets without it. There was a curfew from 5 p.m. to 8 a.m., no Jews in the street.”

The Lodz Ghetto: Many Jews, Little Food

Soon the Nazis issued a decree that Jews had to leave their homes and businesses and go live in a ghetto. The Weinreichs carried their furniture on sleds into the Lodz ghetto, where they lived packed tightly with tens of thousands of other Jews.

Perched on the seat of his walker 80 years later, Sam Weinreich explains: “The Lodz ghetto was surrounded by barbed wire. Everybody had to work. I was assigned to a factory where a cabinetmaker built furniture and we had to finish furniture. At lunchtime we received soup. This was our livelihood.

“We had rations twice a month. People couldn’t live on that ration, it was so meager. After three days they didn’t have anything left to eat. They drank a lot of water.”

His voice choking up and his eyes welling with tears, Weinreich adds, “My mother, my brother and my young sister could not live on this ration.” They died in the ghetto from hunger.

By the summer of 1944, Lodz was the last ghetto remaining in Poland. The Jews there had been working as slave laborers for the Germans for four years. “Busy supplying the German war machine with equipment and the German civilian economy with consumer goods, they continued to work until the last moment,” according to Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center.

Sam, an older sister and his father had been scratching out an existence in the Lodz ghetto for four years, sleeping in their clothes for warmth. “We didn’t know anything about what was going on outside.”

They didn’t know the Germans planned to liquidate the ghetto into extermination camps.

The liquidation of the Lodz ghetto began again in earnest on August 7, 1944. The trains, this time, were headed for Auschwitz, sealing the fates of the Jews of the Lodz ghetto.

Bread and Honey Lures Laborers onto Trains

Weinreich recalls: “They told us they needed laborers to work. We’d have it better there. If you went on the train you’d get bread and honey. My father said, ‘Save yourself. I cannot leave. Maybe it’s what they say it’s going to be.’ My older sister, Chava, said, ‘I’ll stay here with Daddy.’

“I put on my best clothes and I went to the train. We received bread and honey, which you could cut with a knife. We stuffed our stomachs full. We got pushed into the cattle cars, like sardines. We could not get out.”

People relieved themselves in their pants. The smell was unbearable. When the train finally stopped, a “greeting committee” of kapos, or trustee inmates who spoke Yiddish and Polish, ordered the prisoners to undress halfway.

Josef Mengele, the infamous German officer and physician also known as the Angel of Death, looked over Weinreich and selected him for work.

“He decided who shall live, who shall die,” says Weinreich, his eyes tearing and voice quivering.

The kapos commanded Weinreich and other new arrivals to remove the rest of their clothes, then shaved off all their hair to prevent lice. “I didn’t have my clothes anymore.” After a shower, the men ran into another building where they grabbed pants and a jacket with a number on it. “This was my name; that number was my name.”

Weinreich was only in Auschwitz about one week. Then he was transferred to the German concentration camp Dachau, where the Nazis needed labor. He carried cement on his back to build underground airplane hangars for the Germans.

“They counted us every morning before we went to work. It was cold. We stood like chickens, one next to the other, warming up.”

Dying for a Potato

Weinreich describes an unforgettable moment from his work detail. While walking along, he saw a potato on the road. He picked it up and quickly stuck it down his pants, which were secured by a rope at the bottom to keep out the cold air.

A guard looked over and asked, “What do you have there? Open up.” Weinreich opened his pants and the potato fell out. The guard hit him in the face, smacking him to the ground. Then the guard kicked him in the mouth with his boot and knocked out seven teeth.

“I lost seven teeth because of a potato,” he says, weeping at the memory.

People wonder how he survived the Holocaust. He seized opportunities, such as saying yes when a friend asked him to entertain a Jewish doctor who had access to the concentration camp kitchen. With his Yiddish songs, Weinreich would earn soup and an extra piece of bread.

By the time of his liberation on May 8, 1945, Weinreich was his family's sole survivor.

He met Frieda in a displaced persons camp in Landsberg, Germany. He noticed her right away and decided she was the girl for him. They married in the DP camp on his birthday, Sept. 3, 1946.

The Weinreichs moved to America in 1949. They created a life and new family in Memphis, which has been home ever since.

“I’m one of the last survivors of this gehinnom (hell). This is why I’m trying to be available to people. I feel I’m the last of the few people who still remember everything,” he says.

[Published on Aish.com, October 9, 2019]