Ben Hirsch’s life story reads like an adventure book. Separated from his family at age 6. Hiding out in chateaux and villas turned into caring homes in France. Taking a train across the Pyrenees Mountains through Spain. Staying overnight in a convent. Journeying to Portugal. Setting sail aboard a Portuguese ocean liner found to have two stowaways hiding in the coal compartment who had escaped from prison. Almost getting blown overboard by gale-like winds. Landing in America with few belongings. Scratching his way through foster homes and navigating a foreign language, customs, schools and a few bullies to start a new life.

Forget Huck Finn or Harry Potter. This is the true tale of a German boy left orphaned by the Holocaust.

Now 82, Ben Hirsch of Atlanta, Georgia, is happy to retell it. The memories of his early life remain fresh in his orderly mind. An acclaimed synagogue and church architect, father, grandfather and great-grandfather, Hirsch asserts that home is where you find it. In fact, he used that theme as the title of his second book of memoirs.

Less than a month later, the five elder Hirsch siblings left for Paris on a kindertransport (escape train for Jewish children). Kathryn Close’s book “Transplanted Children, A History,” sets the stage: “Many Jewish parents in Germany, appalled at the grim future held out to their children in their native land, sought to send them out of the country.”

In December 1938, Ben was taken in by a kind Jewish couple in Paris, Nathan and Helen Samuels, who soon needed to go into hiding themselves, as Germany invaded France.

“The Germans were coming to Paris, so we had to get on the other side of the green line, the boundary between the free zone and the zone occupied by the German army. Paris was in the occupied zone,” explains Hirsch.

The Samuels moved him to one of the children’s homes outside of Paris for Jewish refugees who had escaped Germany without their parents, the Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE) homes.

“If I hadn’t been there, I would have been picked up,” Hirsch says. “I wasn’t with my parents. I wasn’t with my siblings. I was a waif.”

Under a pact with the Vichy government of France, the Nazis would not attack OSE homes, as long as the children residing there were turned over when they reached age 16. However, the Nazis broke the pact in 1942, when they attacked the OSE homes and in effect closed them.

At first, Hirsch didn’t know where his older siblings were, although they knew where he was sheltered. “I never got any correspondence; all the correspondence from my parents went to the older kids. I have letters in my possession now that I got copies of from my brother Asher and my sister Flo.”

Escape to the United States

After hiding, separated for 2½ years until his last three months in France, Hirsch and his brothers and sisters ultimately escaped to the United States. Alas, their parents, as well as Werner and Rosalene, a younger brother and sister who were infants at the time the elder siblings were sent away, perished in the Nazi death camps.

Two small groups of Jewish children from the OSE homes were able to escape Europe on a Portuguese liner and arrive at New York Harbor. Hirsch was supposed to be on the first ship with his two brothers in June 1941. However, he was forced to stay behind due to stomach cramps diagnosed as appendicitis. “The fact of the matter was that when I first arrived in Marseilles and noticed the lines for hot soup and hot bread, I was so excited that I went from one line to the other several times.” Hot food had been a rarity at the last OSE home where he lived.

A fierce wind almost blew him overboard. He grabbed a post and held on for dear life.

As soon as his stomach recovered, Hirsch went to a kosher OSE chateau outside of Vichy where his sisters Flora and Sarah had been living for several weeks. The trio soon left on the second convoy from Lisbon, aboard the S.S. Mouzinho. One night Ben sneaked upstairs to the ship’s bow. A fierce wind caught him and almost blew him overboard, but he was able to grab a post and hold on for dear life. One of the stewards heard him screaming and came to his rescue.

By the time he arrived in the United States in September 1941 at age 9, weighing 43 pounds, Hirsch had lived in five other countries.

“I had heard and anticipated that the streets would be paved with gold and that President Roosevelt would be on his white horse riding around, checking on people,” Hirsch recalls. “Of course, President Roosevelt was in his wheelchair, crippled by polio.”

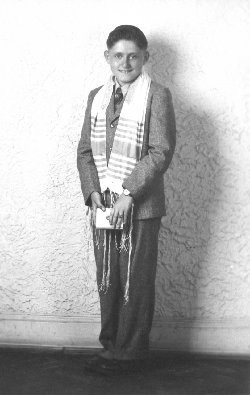

He and his sisters were anxious to rejoin their brothers, who were already living in a foster home in Atlanta, Georgia. All five had received religious training from their parents in Germany, and Ben still observed the Sabbath, kept kosher and wore a kippa. He had worn tzitzis previously, but they were taken from him at a youth camp in France, in an apparent attempt to help him avoid standing out as a Jew and being captured.

The Hebrew Orphans Home/Children’s Service Bureau placed Ben in an Atlanta foster home where his brothers Asher and Jack had been staying after arriving on the first ship from Portugal. The bureau placed their sisters with another Jewish family across town. That arrangement lasted nearly one year, until the family requested to have the boys moved elsewhere, in large part because the foster father was sick. “Leaving a foster home comes with strains of separation,” Ben says.

He would leave three more foster homes before finally feeling secure when his sister Sarah was able to take him in after she got married during his senior year of high school.

Jew Marching to a Different Drummer

Although raised in a religious home in Germany, Ben had abandoned his kippa after two incidents in elementary school. A Jewish third-grade teacher once made him stay after class to chide him for “embarrassing” all the other Jewish children by sporting a kippa. When a bully grabbed it on the playground, Ben ultimately didn’t wear it anymore at school. “I was causing too much angst,” he says in retrospect.

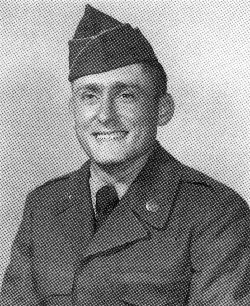

Several Christian soldiers asked him questions about Judaism. He wasn’t happy with the depth of his knowledge and vowed to learn more.

Later, marching to a different drummer in the Army, he would realize the price of working so hard at being the typical American boy. Hirsch, who as a young man bore a resemblance to movie star Kirk Douglas, had been going to chapel, and word got out that he must be a practicing religious Jew – even though he had not been keeping kosher or putting on tefillin (phylacteries). Several devout Christian soldiers sought him out with questions about Judaism. Although he was able to answer these questions to their satisfaction, he wasn’t happy with the depth of his knowledge and vowed to learn more.

The Army experience marked a turning point in his Jewish life. He made up his mind to return to practicing Judaism – keeping kosher and being Sabbath-observant again. He thought to himself, “How could I give up Judaism when so many people, including my parents, died for it?”

Hirsch kept his commitment to God and himself. After leaving the Army and marrying an Atlanta belle named Jacqueline Robkin, he established a kosher home and started wearing tefillin once more and eventually donned tzitzis. Together they embraced a spiritual journey devoted to Torah and mitzvot.

Monumental Life

“Gentle Ben,” as he is known on the basketball court, designed the seven-level home where they have lived since 1966 and raised a family of four. Upstairs in his office, photos attest to a purposeful career. Hirsch designed about two dozen synagogue and church projects, including sanctuaries and additions, from Washington, D.C., to Clearwater, Fla. Perhaps his most important project was done gratis: a Memorial to the Six Million built in 1965 at Greenwood Cemetery in Atlanta. Three years later, the memorial won a national design award – Hirsch’s first one. In 2008, the U.S. government added the structure to the National Register of Historic Places. More importantly, however, the memorial provides a place for Holocaust survivors to say Kaddish during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur for loved ones whose final resting place is unknown.

His Holocaust memorial won a national design award.

Hirsch believes he fulfilled one of his life purposes by designing the memorial at age 32. “I’ve gotten calls from people who saw it, from nuns to professors, and said, ‘I’m so glad you did that, because I never knew anything about the Holocaust.’ ”

His contributions to the community also include leadership. Rabbi Emeritus Emanuel Feldman, who founded Congregation Beth Jacob, an Orthodox shul, more than 50 years ago, calls Hirsch a man of great integrity. “He was a very fine president of the synagogue. He was a steady hand at the helm. He was always thoughtful, deliberate, considerate and even-tempered.”

The rabbi marvels at Hirsch’s journey: “Here’s a kid who survived Europe, was sent to France to escape the Nazis without his parents, came to America, was raised in foster homes, became an architect, fought his way up, struggled, and raised a fine family, all out of sheer willpower, strength and faith. He’s an example of what you can do when you really want to do something and believe in God and your heritage.”

“Even though I did not personally suffer through the camp experience, just being torn away from home and family, being shuttled from place to place in an attempt to escape the Nazi onslaught, and ultimately being confronted with the death of my loved ones, carries its own form of permanent suffering,” Hirsch reveals in his first autobiography, Hearing a Different Drummer (Mercer University Press 2000).

“The pain of the murder of my family, among six million of my people, is as real as if I had suffered through all of the horrors that I have felt compelled to read, study and speak about all these years.”

Ben, his wife and extended family at a bar mitzvah about 18 years ago

Hirsch often tells his story to help others understand the effects of the Holocaust. One appearance stands out in his mind. He and three other local Holocaust survivors spoke at Temima Richard & Jean Katz High School for Girls in Atlanta. One of the girls asked, “If you had a chance to change your life and not have gone through all you did, would you?”

Without hesitating, he answered, “No, then I wouldn’t be who I am... This is what God gave me for whatever reason. Try to find the good side of everything. It’s hard, but sometimes you have to.”

“Obviously, I would have preferred that my family not be killed and that we not be separated, but that would have required a total change of history with the Holocaust never happening,” he writes in Home Is Where You Find It (iUniverse 2006). “I am who I am because of my experiences, and though the losses have been many, the gains of the next generations begin to shed some light on God’s incomprehensible plan.”

[Published on Aish.com, December 27, 2014]