“Miracle on 34th Street,” a perennial classic this time of year about a man named Kris Kringle hired to play Santa at Macy’s, took poetic license. One of the main characters was R.H. Macy, who actually died in 1877, decades before the story in the 1947 movie took place.

In reality, two Jewish brothers, Isidor and Nathan Straus, had become the sole owners of Macy’s in 1896. They were the first businessmen in America to form a mutual aid society to help their employees with medical care. They had a doctor and nurse on the premises. They also provided picnics and sleigh rides, low-cost lunches and Thanksgiving turkeys for their employees.

The German-Jewish family, who owned Macy’s for a century, became well known for their devotion to social welfare, not only for employees, but also the larger community, nation and Israel.

“Their legacy is of compassion and kindness and a serious commitment to business,” says Joan Adler, executive director of the Straus Historical Society Inc.

“They were very, very employee conscious,” agrees Robert Grippo, author of two books about Macy’s. “They believed in giving back.”

Grippo wrote in "Macy's: The Store. The Star. The Story" that if one of the brothers notices an employee seemed troubled or unwell, he would inquire about the problem and provide whatever assistance was needed, whether it was money, a new suit or a doctor's services. "This sincere interest created a warm family feeling and esprit de corps that was long remarked upon by Macy's employees."

The Straus Family history is a rags to riches immigrant story. Isidor and Nathan’s father, Lazarus, immigrated to the United States in 1852, following the 1848 revolution in Germany and the economic difficulties that ensued.

Philadelphia was the center of the German Jewish population at that time, but Lazarus was told he would find better opportunities in the South. He made his way to Oglethorpe, Ga., where fellow German Jews set him up as a pushcart peddler to the plantation owners. By 1854 he had opened a dry-goods store in Talbotton, Ga., and sent for his wife Sara and four surviving children. A fifth child had died at age 1½ years old.

In 1863 they moved to a larger town 40 miles away, Columbus, Ga., where they became successful merchants. Yet they couldn’t feel comfortable in the shadow of chaos once again: the Civil War.

At the close of the war in 1865, much of Columbus was reduced to ashes. Lazarus moved his family to New York, opening a company that imported china, porcelain, glassware and crockery. The firm became known throughout the world.

In 1873 the Strauses convinced Rowland H. Macy to allow them to run a concession in the basement of his store on 14th Street. By 1884 they were part-owners of R. H. Macy’s & Co., and by 1896 they were the sole owners.

More than any other, Isidor was the man who made Macy’s.

Like Macy’s, Isidor’s star was rising. More than any other, he was the man who made Macy’s, according to Joan Adler. ”They had a huge house on W. 105th Street with the first indoor porcelain bathtub.”

Isidor was also a U.S. Congressman from 1894-1895. He was asked to run for re-election but declined, stating his responsibilities at home were great and he didn't believe he could do both. Although he never held a New York City office, he was active in many organizations that supported the commerce and industry of the city. He also devoted his time to philanthropic organizations.

(Courtesy of Straus Historical Society)

He helped establish Montefiore Hospital and the Educational Alliance (Settlement House) in New York. The latter began as a place for immigrants in congested tenements to learn how to acclimate to the United States. All told, the alliance has helped 4 million New Yorkers of diverse backgrounds.

The Titanic

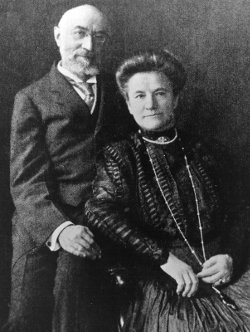

Isidor was at the helm as president of Macy’s until he and his wife, Ida, died on the Titanic when it hit an iceberg and sank in 1912.

Mrs. Straus had a chance to be saved from the Titanic but she refused to leave her husband.

“Mrs. Straus had a chance to be saved, but she refused to leave her husband,” a Titanic survivor reported, explaining that lifeboats rescued women and children first. “As our boat moved away from the ship, the last boat of all, we could plainly see Mr. and Mrs. Straus standing near the rail with their arms around each other.

“The lights of the Titanic were all burning and the band was playing. To me the most affecting episode of the whole disaster was that final glimpse of this elderly couple awaiting the end together.”

“Their lives were beautiful and their deaths glorious.” The sentiment long graced a plaque inside what became known as Macy’s Memorial Entrance, on 34th Street in New York.

Newspaper headlines like “Mr. and Mrs. Straus Go Down with Arms Entwined” riveted readers. More than 2,000 people packed Carnegie Hall to pay their respects and hear tributes to the Strauses. An estimated 40,000 attended a memorial service at The Educational Alliance.

A New York Times obituary recalled Isidor as a director in many and supporter of almost every philanthropic institution in New York.

That remains the family’s legacy several generations later – as individuals and business and community leaders.

Adler calls them an “unbelievably high-achieving family who are very mindful of the opportunity they’ve been given and believe in paying it forward.”

Nathan Straus’s Legacy

Isidor’s business partner, his brother Nathan, brought pasteurization to the world. He may have become interested after a cow on his farm died of tuberculosis. He learned Louis Pasteur’s heat process to kill bacteria in liquids and hired scientists to build a laboratory to make clean milk. Then he created depots across New York to distribute pasteurized milk at low or no cost.

Nathan is credited with saving the lives of countless babies.

“It is due entirely to your campaign for the purification of the milk of the city of some years ago that the Health Department has been able to report recently that the mortality figures have been cut just in half. One infant out of every two in New York owes its existence to you,” the mayor of New York told him.

The Israeli coastal city Netanya was named in honor of Nathan Straus.

An avid Zionist after his first trip to Palestine in 1904, Nathan built food pantries and helped found the Joint Distribution Committee. He provided money for the establishment of the Jerusalem Health Center and gave the building over to Hadassah when it opened in 1929. Straus Street in Jerusalem is named in honor of him and his wife, Lina.

The Israeli coastal city Netanya, founded in 1928, was also named in honor of Nathan Straus.

With all their successes, the Straus family has known its share of heartache. “Theirs was an era when children died,” says Adler. “Each of them had children who didn’t make it. I think that was the biggest struggle, health.”

Lazarus, the patriarch who moved his brood from Germany to the United States, had to start over in a new country and then again when he lost almost everything during the Civil War.

A century later, the empire his heirs built was gone with the wind. “The Rain on Macy’s Parade: How Greed, Ambition, and Folly Ruined America's Greatest Store” by Jeffrey Trachtenberg chronicles the takeover of Macy’s by the chairman (who wasn’t related to the Strauses) and a group of board members in 1986. Their leveraged buyout meant the end of a revered business culture.

However, the Straus culture lives on in more than 1,000 family members, according to historian Adler. They continue to donate time and money to worthy endeavors and put a proud face to the Jewish immigrant experience in America.

[Published on Aish.com, December 19, 2015]