The university has apologized for its shameful anti-Semitic treatment of Jewish dental students decades ago.

It was the summer of 1952 and Americans were prospering. Perry Brickman had just completed his first year of dental school in Atlanta, Georgia. During break he was living at home with his parents in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and he opened a letter that would change his life — and from which he would not fully recover for 60 years.

Brickman received word from Emory University School of Dentistry that he had flunked out of its four-year program and he need not bother returning.

A year later, Brickman’s three Jewish classmates were summarily dismissed.

Brickman was stunned and mortified. A B-plus student in biology as an Emory undergraduate, he had earned early admission to dental school and never failed a course in his life. Not once had a professor or the dean called him in to say he wasn’t doing well.

“Back then you just tucked your tail between your legs, brushed yourself off and went about your business,” recalls Brickman, 82, sitting on his living room couch in Atlanta one rainy afternoon. “You didn’t sue back then. Nobody would believe you anyway. Your parents didn’t believe you.”

His parents accused him of goofing off. They couldn’t fathom the idea that Emory might be at fault. The humiliation caused Brickman and many other Jewish men to hide that era of their lives from wives, children, grandchildren, friends and business associates.

A Fraternity of Silence

Shirley, his wife of 60 years, calls it a fraternity of silence. “Some of us who were AEPi fraternity brothers at Emory saw each other from time to time,” relates Perry, father of three and grandfather of six. “AEPi had its 50th reunion in 2000 in Savannah, and we didn’t say a word.”

The silence on both sides was officially broken in October 2012, when Emory apologized for decades of anti-Semitism at its now defunct dental school. In a public ceremony 34 Jewish men and their wives who had experienced that era came together from across the United States. Their children and grandchildren accompanied them. The men finally received the apology they had never thought possible.

“I’m sorry. We are sorry,” said Emory University President Dr. James Wagner to the crowd of approximately 500 at the conciliatory event, which included a screening of From Silence to Recognition: Confronting Discrimination in Emory’s Dental School History.

The Emory documentary drew upon five years of research by Brickman and included poignant interviews he had conducted with former Jewish students whom Emory had wrongfully failed.

“Emory's apology was unique and sincere. After hearing and seeing my findings, Emory, without any pressure, willingly apologized to the world for the damage they had done and the hurt they inflicted,” says Brickman. “Their apology changed the lives and repaired the hearts of everyone who was affected by the discrimination.”

Until then, many of the Jewish men had not admitted aloud how the discrimination had hurt them and dashed their hopes.

“Dirty Jew”

Brickman had dreamed of being a dentist while growing up in Chattanooga during the Great Depression. His Lithuanian-born parents operated a small coal yard where they worked long hours to ensure a good education for their children.

The kind family dentist, with his clean office and state-of-the-art practice, became Brickman’s role model. A family friend recommended the dental school at Emory, so Brickman pursued his undergraduate studies there. “They had two Jewish fraternities. Of course you couldn’t get into any other fraternities. That’s the way we grew up; it didn’t bother us.” Brickman says the young men were unaware that Emory, like other private schools around the country, had a quota system in 1949. “It started up East in the 1920s, when all of a sudden there was such an influx of immigrants. All the first-generation Jews, Italians and others wanted to send their kids to college. These kids were really excelling. The schools instituted quotas because the percentage of these students got up to 25%. We Jewish boys didn’t know we were competing against two cohorts of people: the general pool and the Jewish.” No one griped about the situation; they were just happy to have made the cut. At the time, Emory’s all-male student body was mostly white and Protestant.

In dental school, four of the 80 new students in 1951 were Jewish, including Brickman. Two years later, all four had been booted out. They had first endured insults. Professors would call them “dirty Jew” and accuse them of cheating, and the dean would say, “You Jews don’t have it in your hands.” Faculty members criticized their wax carvings of teeth and physically crushed them or threw them out the window.

Hands-Down Successes

Two years after he retired, Brickman attended a 30th anniversary celebration of Emory’s Judaic studies program. Dr. Eric Goldstein, director of the Tam Institute for Jewish Studies, curated an exhibit that caught Brickman’s attention and sparked his crusade for justice. It included:

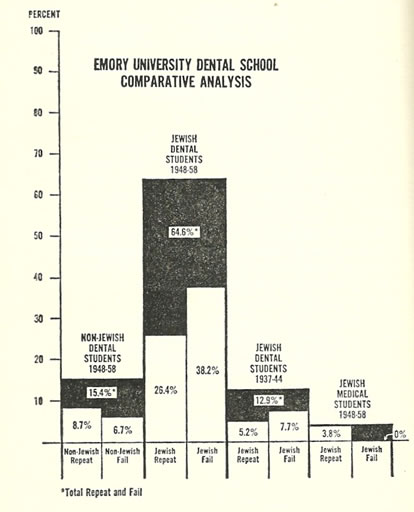

- A bar graph showing a spike in the failure rate of Jewish students from 1948 to 1961. The graph came from gumshoe detective work by the Anti-Defamation League’s former Southeast director, Art Levin. He reported 65% of the Jewish dental students accepted during that time under the deanship of Buhler were either flunked out of school or made to repeat one or more years.

- A copy of Buhler’s resignation as dean in 1961.

- An article in the Atlanta newspaper after the dean resigned, addressing rumors of Emory being anti-Semitic. Then-Emory president Dr. Sidney Walter Martin replied, “Absolutely not. He could have stayed here if he wished.” In early 1961, Buhler decided to require prospective students to specify whether they were “Caucasian, Jewish or Other” on their application form. The ADL’s Levin brought that form to the attention of the Emory administration which forbade its use. But Martin refused to correlate the discovery of the admission form and the dean’s departure.

“It was the first time I’d seen those figures of how many people had flunked,” Brickman said. “It was obvious that it was a systemic problem.”

Two years after Brickman saw the exhibit, his former classmate Burns called him out of the blue and asked how he was doing. “He told me that his experience at Emory dental school had been a burden to him all his life. That really got me thinking, I’ve got to do something!”

Brickman tracked down dozens of Jewish students who had been affected and recorded his interviews with them. Among his plum discoveries were the dean’s memoirs with incriminating evidence about Buhler’s anti-Semitic beliefs.

Other gems included Art Levin’s personal correspondence that Brickman discovered in a warehouse in Brooklyn, revealing the resistance the former ADL Southeast director had encountered from Emory and Atlanta Jewish community leaders.

Thanks to his tenacity, Brickman also found Levin himself, who was 93 and living in Florida. Said Levin: “You know more about me than I know about myself.”

Brickman’s work resulted in his documentary “The Buhler Years: 1948-1961.” His meticulous research prompted Emory to issue the public apology.

At the event, the university presented Brickman with the prestigious Maker of Emory History Award and set up a Brickman/Levin scholarship to supplement Jewish doctoral candidates at the university. “The real hero, Art Levin of the ADL, was the one who pressured Buhler to resign,” Brickman insists.

Brickman is still concerned about Jewish university students, but for different reasons. “Today there is another face of anti-Semitism. Before they kept you out with numbers. Now it’s not a Jewish problem to be able to get into college or medical school or dental school. The problem is what Jewish students on college campuses are facing with anti-Israel and anti-Semitic sentiment.”

He urges students, parents and alumni, in conjunction with Jewish organizations, to actively combat discrimination at every level of the educational system.

[Published on Aish.com, August 1, 2015]