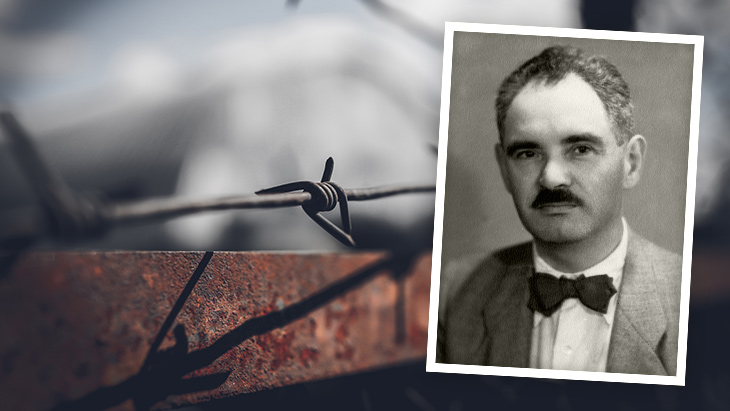

Aron Grünhut, a Jew from Bratislava, Slovakia, saved more than 1,350 lives during World War II.

In 1939 he organized an illegal ship transport to Palestine. The same year he also teamed up with British diplomat and humanitarian Nicholas Winton to rescue 10 Jewish children by railway transport to England, where they survived the war.

“People should know Aron Grunhut didn’t sit around twiddling his thumbs,” his son, Benny, 93, proudly told Aish.com in an exclusive interview from his home in Florida.

For decades, Grunhut’s name passed into oblivion as totalitarian regimes governed Czechoslovakia after it became a reunified country when World War II ended. But in recent years, different organizations have shone a light on his heroism. They include the B’nai B’rith World Center-Jerusalem and the Committee to Recognize the Heroism of Jewish Rescuers During the Holocaust, which in 2011 paid tribute to 175 Jews, including Grunhut, who saved other Jews.

The Jewish Rescuer Citations were designed to show a side of life during the Holocaust not often discussed: that of Jewish resistance.

Perhaps one of the least told stories of the Holocaust is the story of Jews who rescued fellow Jews. Jewish rescuers put their own lives in jeopardy to help other Jews escape the Nazi killing machine,” according to the B’nai B’rith website.

Slovak Government Hails a Humanitarian

Along those lines came a traveling exhibition called “Aron Grunhut: Rescuer of the Jews and Human Rights Defender.” Initiated by journalist Martin Mozer and supported by the Slovak government, it began its journey, fittingly, in Bratislava in 2014.

On the eve of the Holocaust, Bratislava – then known as Pressburg – claimed the largest Jewish community in Slovakia. In 1930 some 15,000 Jews lived in the city, making up 12 percent of the population.

After the creation of an independent Slovak state in the late 1930s, the Jews of Bratislava were subjected to discrimination and persecution, according to Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum. Authorities revoked the licenses of most Jewish doctors and lawyers and fired many Jewish public officials. Jewish students no longer could attend public schools. Many Jews were evicted from their apartments in central areas in the city, and their property confiscated.

By 1942 nearly half of Bratislava’s Jews had been dispersed among smaller towns across the country. Then began deportations to extermination camps in Poland. Most Slovakian Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.

Aron Grunhut relied on business savvy, connections and chutzpah to save as many souls as he could. Born in 1895 in Bratislava to a devout Orthodox family, he traded in various commodities. His contacts and business trips frequently took him abroad.

Grunhut watched the radicalization of the political situation and foresaw the huge danger that Hitler represented to Jews. He decided to act.

In the months following the political union of Austria with Germany, Grunhut saved Jewish refugees from the municipality of Kittsee who were moved to Hungary. He helped them to Slovakia – otherwise they would have ended up in concentration camps.

He had a tent camp built for Jews as people without right of domicile and even organized their journeys to Palestine.

Cutting Deals with a Gestapo Lawyer

He met with a Gestapo lawyer in Vienna to secure the release of Bratislava clothing merchant Juda Goldberger, who was kidnapped and transported across the border.

One of Grunhut’s most dramatic rescues occurred in 1939, when he arranged for an illegal transport of Jewish refugees to Palestine. He negotiated with the Nazis to allow imperiled Jews to escape to safety.

He started planning the rescue in June of that year. By the end of July he had chartered two river steamboats, the Queen Elizabeth and the Tsar Dusan. They departed from the Bratislava port with 1,365 Jewish refugees, not only from Slovakia but also Hungary, Poland, the former Austria, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

Boats en route to Palestine faced danger negotiating Europe’s rivers.

“They sailed down the Danube to the Bulgarian city Ruse, from where they were supposed to travel by train to Varna,” according to the “Aron Grunhut” exhibition.

Grunhut planned the voyage to take six days altogether. However, Bulgarian frontier guards stopped the steamboats with the refugees and intended to send them back. They spent more than four weeks aboard in international waters. Finally Grunhut persuaded Bulgarian offices to allow the ships to continue. Then in the Romanian port Sulina, the refugees changed to the cargo ship Noemi Julia. After 83 distressful days filled with worries, the Jewish refugees arrived in Haifa.”

Grunhut bravely slayed many dragons that stood between him and success. In delivering the refugees to Palestine, he evaded a strict quota on Jewish immigration in the most desperate of times as set out by the British White Paper of 1939. Palestine was then under British Mandate control.

Like Schindler and Winton

He has been compared to Oskar Schindler and Sir Nicholas Winton, renowned saviors of Jews during the Holocaust.

Grunhut made contact with Winton, a diplomat and banker in Britain born to German-Jewish parents, who organized railway transports to save children from Hitler. The two men consulted with Jewish communities and rabbis to select a group of children to travel from Bratislava on a transport to England.

Ten boys from Orthodox families made it to London in June 1939 and survived the war there. They included Tibor Weiss (now Yitzchok Tuvia Weiss), who became Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem, and Grunhut’s son Benny, now a grandfather and retired architect who outlived his four brothers.

Aron Grunhut remained with his family in Bratislava during the first years of World War II. He stayed active in the Jewish resistance. In 1943 Slovak authorities arrested and locked him in jail for several months. Meanwhile, his wife, Etel, and youngest son escaped to Hungary.

Life in Hiding

After his release from prison, Grunhut crossed the border to Hungary in secret to live undercover with his family. When the Hungarian secret police discovered Grunhut in 1944, a brave firefighter named Emanuel Zima hid his family in the cellar of the former Czechoslovak Embassy occupied by Germans in Budapest. Other Jewish refugees were hiding there. All survived until the Soviet army liberated Czechoslovakia in 1945.

When the war ended, the Grunhuts returned to Bratislava. Aron started exporting goose liver to France. Following the Communist coup in 1948, they emigrated to Israel. The community-minded Jewish hero led groups like the Society of Former Bratislava Citizens in Israel and the Association of Chatam Sofer, honoring the founder of a celebrated yeshiva in Bratislava.

Grunhut died in Tel Aviv in 1974 at age 79.

‘Aron Grunhut Saved My Life’

“He was a great man. He was a great father,” says Benny Goren-Grunhut, who Hebraicized his last name. “My mother was such a lady. She worked hard in the family restaurant so my father could do mitzvot.”

Goren-Grunhut cherishes a letter he received from the Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem who was on the kindertransport with him. “My dear Benny, I never knew your father was Aron Grunhut, who saved my life. Come and visit me. If you come, you will be my only guest for two or three hours.”

Delightedly, he recounts: “I told the rebbe, ‘My father isn’t here anymore. I need someone to bless me.’ The rabbi blessed me. We became good friends.”

[Published on Aish.com, October 3, 2021]