Prof. Rabbi Dr. Richard Freund, the Maurice Greenberg Professor of Jewish History at the University of Hartford in Connecticut, is most passionate about his search for Holocaust escape tunnels and buried synagogues.

Dr. Freund is spending his summer paying tribute to lost Jewish communities in Rhodes and Vilna. In their day, the former was known as La Chica Yerushalyim (in Ladino) or the Little Jerusalem and the latter as Yerushalayim d’Lita (in Hebrew/Yiddish) or the Jerusalem of Lithuania.

He will speak on the Mediterranean island of Rhodes on July 24 as part of a major week-long commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the Nazis’ round-up of all the Jews there in one day in 1944.

Rhodes: An Ancient Sefardic Community Wiped Out in One Day

“Rhodes is a totally different Holocaust story. It’s Sefardic,” Freund recently told Aish.com. “Jews had been there 2,300 years. The Nazis put them on a train to Auschwitz and basically ended the history of Rhodes Jewry.”

About 10 Jews live in Rhodes today. Freund is doing archaeological work on three synagogue sites there. He uses a noninvasive method called geoscience, with technologies that show what lies underground.

“Although it is a place I had heard about for most of my life, I thought that my Rhodian experience would simply involve working on the large amount of Rhodian pottery that we found in our Israeli excavations. But in the end, I went to Rhodes to uncover evidence of what happened to their synagogues before, during and after the Holocaust, and in the process recovering much about who these Jews were,” Freund writes in his new book, “The Archaeology of the Holocaust: Vilna, Rhodes, and Escape Tunnels” (The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Lanham, MD, 2019).

He started with one mystery at the Kahal Shalom Synagogue, which related indirectly to the Holocaust. The site was damaged during the Holocaust but reconstructed as a museum and historical society in the last 30 years thanks to the generosity of ex-patriate Rhodesli (the Ladino term of endearment for Rhodes’ Jews) worldwide.

Freund had seen photos of two arks and a central door between them found in the main prayer hall of the Rhodes synagogue.

“The two arks are serviceable – Jews could read as many as three Torah scrolls for a holiday or Sabbath, and the arks could easily accommodate multiple scrolls – but require that the leader know exactly which ark contains the appropriate Torah scroll to be read in what order at the service,” he writes.

As for the door, “It is, as one Rhodesli told me, ‘an additional exit, just in case!’ – implying that the Jews did indeed think about security, even during earlier periods.”

Freund sees a bridge between the Kahal Shalom Synagogue layout and art from earlier synagogues. The art depicts a pilgrim vision of the Temple of Jerusalem with two small, mirror-image ark-like structures leading into the Temple with a door in the center.

“These openings are not arks in the Temple, but rather they depict the pilgrims’ last view of the Holy Temple as they left for the diaspora. There is a synagogue type with this configuration in Sardis and in other ancient synagogues. The Rhodesli were literally praying toward a more architecturally accurate view of the second Temple every day.”

The Vilna Great Synagogue Has Risen

Director of the University of Hartford’s Maurice Greenberg Center for Judaic Studies, Freund is also spending his summer break excavating in Lithuania. The interest is personal as well as professional. He traces his heritage to Litvak Jews who left at the end of the 19th century.

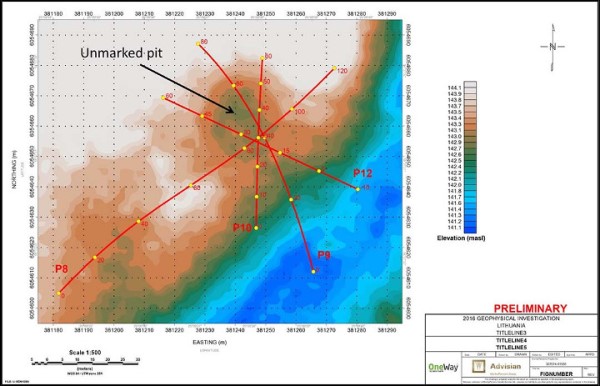

Among his projects are the Great Synagogue of Vilna and a Holocaust escape tunnel in the Ponar forest. Freund is a pioneer in the use of ground-penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tomography to noninvasively map the surface at sensitive sites worldwide for traces of structures and burial grounds.

“The discovery that the Great Synagogue of Vilna was still possibly lurking below the surface of modern Vilna was what brought my research team to Lithuania,” the 63-year-old author explains in The Archaeology of the Holocaust.

Vilna was once an epicenter of Jewish culture in Europe. Almost 40 percent of the population was Jewish.

The Great Synagogue seated thousands of people and had a huge courtyard, mikvahs, a large bathhouse, 12 small prayer houses, and one of the world’s most famous libraries. “It was for all intents and purposes the Vatican of Europe for 300 years.”

The Nazis had only partially destroyed it, Freund told Aish.com. But the secret of the Great Synagogue was that the main sanctuary was located below street level. Following the ecclesiastical custom of the times, the builders could not make the synagogue higher than a local church. So Instead of building up, they built down – placing two stories of the main sanctuary below the ground.

After the war the Soviets demolished the last standing walls, unwittingly sealing the synagogue remains underground. An elementary school rose on top of the religious site. Freund, his students and crew mapped the entire subsurface and found the synagogue.

Because of that, in 2018 the Lithuanian government closed the elementary school and allowed excavation underneath. The international effort comprises Dr. Jon Seligman of the Israel Antiquities Authority, Dr. Zenonas Baubonis of the Lithuanian Institute for History and Freund’s teams from Canada and the United States.

Thanks to funding from the U.S. Embassy, U.S. Commission for America’s Heritage Abroad, Targum Shlishi, Geoscientists Without Borders, Good Will Fund (foundation) of the Jewish Community of Lithuania and private donors, the work continues this summer with vigor.

“They’re thinking of making the entire thing into a museum,” Freund reports. “Last year we found the bima, and the second of two beautiful mikvaot. This summer hopefully we will discover more things.”

New Technology, Old Secrets

Freund uses modern technology to unearth old secrets. Ground-penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tomography allow his team to do noninvasive archaeology. The former signals when something is lurking below the surface. The latter identifies the type of material buried there.

“There are very few Holocaust survivors left. In a very short time, we won’t have any survivors. I think the new frontier will be science.”

forest looking for mass burials in a forest

in northeastern Lithuania.

He has directed six archaeological projects in Israel and three projects in Europe, including Bethsaida, Qumran, the Cave of Letters, Nazareth, Yavne, Har Karkom (Mount Sinai), plus a research project at the extermination camp at Sobibor, Poland. He was called in to look for the lost city of Atlantis, an expedition captured by the National Geographic Channel’s documentary “Atlantis Rising.”

His theory? A tsunami destroyed Atlantis.

With the expensive equipment and staff he brings, Freund provides all of the major museums and archaeology institutes in the host country a chance to present proposals. “If we can do the project, we offer equipment and services for free to spread the methodology and create new colleagues in the field.”

Holocaust Escape Tunnel

That’s how he came to discover a Holocaust escape tunnel in the Ponar forest in Lithuania just as his archaeological work started at the Great Synagogue.

The Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum suggested he search for mass burial sites in the forests around the Ponar killing fields.

“We accepted the proposal as an add-on. They told us this near mythological story about the Holocaust escape tunnel from one of the mass burial pits. There was testimony but no concrete evidence. How can you find a tunnel buried 20 feet below the surface in the midst of so many mass burials adjacent? We said we would try. We found it on the first day!”

Today a serene park there belies the bloody history of the area.

The Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators brought 100,000 victims, including 70,000 Jews, to the Ponar forest and shot them in the pits. In the end they conscripted 80 Jews from surrounding camps to burn the bodies and destroy evidence of the atrocities.

The group of Jews in shackles was known as the Burning Brigade. As if their work weren’t horrific enough, they knew when they finished it, they would be the last victims. By night they built an escape tunnel using only spoons and their hands.

On the last night of Passover, April 1944, several brigade members escaped through the tunnel. “A lot of people don’t realize how much Jews resisted the Nazis and how much courage they had,” declares Freund.

The PBS science series NOVA filmed as Freund’s team discovered the Ponar escape tunnel. Children of the survivors heard about the documentary. An emotional Hana Amir, daughter of a survivor who escaped Ponar at age 17, told PBS, “To do what they did, that is heroism. It’s unbelievable.”

Ten million people have seen the “Holocaust Escape Tunnel” documentary. According to Freund, “It never ceases to affect people. It’s the ultimate hope against hope, that you’re able to get yourself out of the worst possible circumstances.”

[Published on Aish.com, July 6, 2019]