An adult woman raised as a Christian discovers that her parents were Jewish Holocaust survivors.

Imagine growing up in a Presbyterian family, being baptized in a church, wearing a gold cross, celebrating Christian holidays, having a minister perform your wedding—and then learning as an adult that your parents really were Jewish.

In 1994, Orlene Allen Gallops’ family research led her to the discovery that her parents hid their Jewish roots and took them to their graves. The 69-year-old consultant recalls the seismic shift in her world in her book, “Hiding in Plain Sight” (Two Ems Press, Madison, CT 2021)

As her European-born mother, Eleonore, lay dying from early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, the care facility in Maryland needed proof of her date of birth. In the absence of a birth certificate, Orlene sent away to the New York City Department of Vital Statistics to obtain a copy of her parents’ marriage certificate.

When Orlene received it, she couldn’t believe her eyes. A rabbi, Zeidel Epstein, had penned his signature at the bottom.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, they really were Jewish!’” Orlene told Aish.com. “This answers so many unanswered questions about their background.”

As Orlene would discover, Larry and Eleonore Allen not only were Jewish, but they had escaped the Holocaust that killed most of their family along with millions of others. Then they sealed their hearts tightly and left that world behind.

Proud Americans Haunted by the Old Country

Eleonore Brahm married Larry Allen in 1949 when she was 20 and he 34. He had shed his Slavic name Ladislav Adler while serving in the British Army after escaping from Czechoslovakia in 1939.

Meanwhile, Orlene had grown up hearing that her mother was born and raised in France. “We later found out she was born in Germany. She never divulged that. I think she spent most of her childhood in France though.”

The Allens met in Paris and came separately to the United States, which they adopted as their homeland. After marrying in the U.S., they welcomed two daughters: Susan and Orlene.”

Larry’s work as a radiologist with the Veterans Administration took the family around the country until they ended up in Washington, D.C., in the late 1950s. The girls were baptized in a Presbyterian church there. The minister, a close family friend, later presided over their weddings in the church.

In the late 1960s, the family moved to Forest Hills, N.Y.—a Jewish neighborhood, it turned out. People had last names like Epstein and Goldstein. Orlene was surprised that nobody was going to school on the Jewish holidays. “I’d say to my mother, ‘I don’t want to go to school because nobody’s going to be there.’ She’d say, ‘You have to go because you’re not Jewish.’”

Despite her mother’s protestations, Orlene learned a lot about Jewish holidays in high school. She went to a friend’s Passover seder and loved it.

In hindsight, Orlene can see that “there were many inklings of being Jewish but they never told us they were Jewish.” For instance, her mother would say not to drink milk with a salami sandwich. Her father would say, “There’s no such thing as the son of God,” despite what the girls learned in Sunday school at church.

Orlene remembers feeling conflicted by the mixed messages. When she and her sister questioned their parents, they were told: “Sometimes it’s better to let sleeping dogs lie. Look forward not back.” The Allens never returned to Europe; Larry claimed he might be jailed or shot if he did.

Unravelling the Truth

The truth started unraveling with the receipt of the Allens’ marriage certificate as Eleonore was close to passing away in 1994, five years after her husband’s death.

Orlene, a single mother who was rearing a daughter and completing graduate school, didn’t yet have the Internet resources to do the type of research available today.

However, she did seek out a rabbi in West Hartford, Connecticut, armed with her parents’ marriage certificate and father’s records from medical school in Bratislava found in his safe that also confirmed he was Jewish. The rabbi said, “There’s no doubt your parents were Jewish. A rabbi in 1949 would not have married two people where one wasn’t Jewish.”

Why Didn’t They Tell Us?

Orlene’s mind began spinning. Why didn’t they tell us? Who were my family? Even if they converted to Christianity, why didn’t they share this with us when we were older? It never once came up!”

She believes the answers are rooted in fear. Her deeply protective parents probably had an intense desire to shield their children from their painful history, as well as from bias and discrimination.

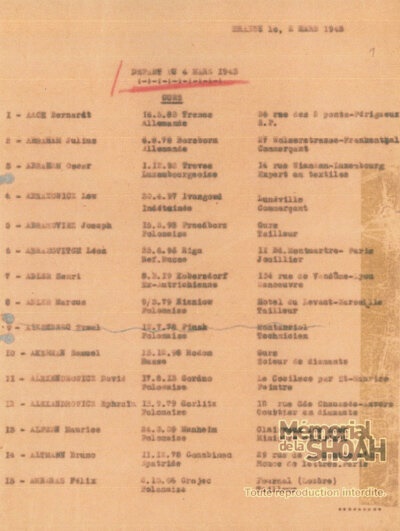

(Oskar Abraham-Brahm) appears, the third name on the list.

Courtesy of the U.S. Memorial Holocaust Museum

Now a grandmother of three, Orlene harbors no anger at being kept in the dark. Rather, she feels only sadness for what her parents experienced—believing they had to give up who they were and to dismiss their faith.

“I’m always grateful that I got picked to be their daughter,” she says. “I always knew how much I was loved. Whenever I walked in or left the house, my mother would kiss me. I was raised in an atmosphere of love. It was obvious they were in love with each other.”

Getting a Clue

After Orlene retired 10 years ago, her family research kicked into high gear. With her husband, John, gently encouraging her, she sleuthed on Ancestry.com, JewishGen.org and YadVashem.org and traveled to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and Prague. Sadly, with only two exceptions—paternal aunts in the U.S. and Slovakia—Eleonore and Larry’s families had all perished in the Holocaust.

The research also took Orlene and her sister, Susan, to Vancouver to meet her Aunt Blanche’s stepdaughter, Judith. “She had a box full of pictures and documents she’d discovered in my aunt’s place in Florida after she died. That was the most wonderful find,” says Orlene.

Date is unknown.

“The pain of knowing that my Aunt Blanche had survived four concentration camps and lost her husband, Zoltan, who was murdered by the Nazis was cushioned by the knowledge that she found the love of a man (Judith’s father) and his children.”

After years of research, Orlene now trains her energy on Holocaust education. She speaks to elementary schoolchildren, book clubs and library groups to make sure people will never forget.

Does she feel connected to Judaism in other ways? Orlene muses: “I met a woman in Slovakia who asked me how I feel about being a Jew, because if your mother’s a Jew, you’re a Jew. I said to her, ‘I’m proud to be my mother’s daughter and feel anguish about what she experienced. I’m happy she survived and found love and happiness with my dad.’

“After my book was published last year, I wanted to learn more about Judaism. I still feel the conflict between what I learned in church and the teachings of Judaism. But I think the conflict is a way to grow and ask questions. That’s the way we learn.”

Orlene’s book is available at https://www.amazon.com/dp/1734368926/friendsofaishhat

[Published on Aish.com, September 25, 2022]