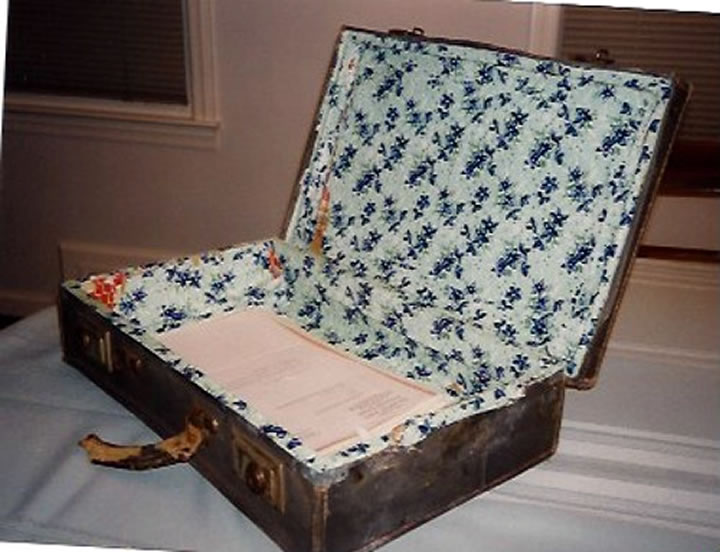

Paula Neuman Gris’s 75-year-old blue suitcase is an old friend. It accompanied her from her childhood home in Czernowitz, Romania, to the killing fields of the Holocaust to a displaced persons’ camp in Germany and across the ocean to America.

The suitcase held necessities and secrets. The journey began in 1941 when all the Jews of Czernowitz received the dreaded order to pack two bags and be ready to leave in two hours. It was part of the Romanian government’s directive to “cleanse the Earth” of Jews.

A year previously, after the Russians had occupied her hometown of Czernowitz, they seized her father, Simon Neuman, a men’s haberdasher, as a slave laborer. “They arrested my father because he was a capitalist. They had their own political agenda. He was imprisoned. At that time, my mother was pregnant with their second child,” Paula says in an Aish.com interview.

Her mother, Etka Neuman, would leave three-year-old Paula alone every day to visit him in prison and take him food. Then Simon disappeared with 10,000 Jewish men whom the Russians deported to Siberia. What became of him from there is unclear.

Meanwhile, Etka bore their baby. Anti-Jewish laws and a curfew were in force. Jews couldn’t be admitted to public hospitals and weren’t supposed to leave their homes at night. However, Etka went into labor at night, so she risked her life and sneaked out onto the street to reach her Jewish midwife.

“My memory of that night was she left me alone – probably saying, ‘I love you, I have to leave now.’ She locked the door and went away. My memory was standing frozen as a three-year-old little girl, looking at the doorknob all night long. It was probably the beginning of a long period of experiencing terror and fear and the sense of helplessness,” recalls Paula.

Her mother made it to the midwife’s where she spent the night. The next morning she wrapped up her new baby in a blanket and walked home.

Childhood Ends at Age Three

Paula declares that her childhood ended at that point. “I became my mother’s partner until the end of the war in protecting and keeping that child alive.”

One-quarter of a million Jews died of execution, disease and starvation in Transnitria.

Her mother managed to obtain an exemption written by the town mayor and allowing them to remain in the ghetto for nine months after the order came in November 1941 to transport Jews to the Romanian-administered territory called Transnitria, what Paula describes as the largest killing field of the Holocaust. One-quarter of a million Jews died of execution, disease and starvation there.

November was the coldest month on record in years and many Jews piled into cattle cars froze to death in transit. Waiting nine months for the transport in June when the weather wasn’t cold would give her baby sister Sylvia a better chance of survival.

The Last Time I Cried

Paula remembers the little blue suitcase’s role. Her mother was allowed two suitcases, but needed one hand free to carry Sylvia, so she took just one suitcase packed with photographs, documents, diapers, a towel and soap. In the corners Etka stuffed money and jewelry with which to bribe officials if necessary and they left home.

“I’m sure I must have said, ‘Can I take my blanket? Can I take my bear?’ Instead, I had to carry a soup can. I think that was probably the last time I cried,” says Paula.

Suitcases remain etched in her memory from the eyes of a child. She recalls masses of people pushing toward the transport to Transnitria. Running, she held onto her mother’s skirt. “You had to keep moving, otherwise you’d get trampled.”

With her mother performing backbreaking forced labor for the war effort in the rock quarries of Transnistria, Paula was the sole caretaker of her baby sister during the day. The girls learned to hide and stay quiet in the vacated hut they occupied. Fear and hunger left them with no energy to play, with one day blending into the next, unbroken by birthdays or holidays.

“I don’t remember very much of it except sheltering my sister, waiting in an abandoned house for my mother to come back, not crying.”

“There was a very long darkness. I don’t remember very much of it except sheltering my sister, waiting in an abandoned house for my mother to come back, not crying, being a caregiver to my sister, being as grown up as I could possibly be, which means trying to stay brave.”

Immediately after returning home from work every night, Etka would wash the girls’ clothes in a stream. As Paula explains, “Cleanliness was medicine for us, keeping off bedbugs and lice. After that my mother nursed her baby. The three of us slept in a cot together.”

The family survived like that for two years, with little food and no medicine. Paula learned to delay gratification. If she had a slice of bread, she never ate it all at once. Had the Germans not retreated from the Russians, she doesn’t believe her family would have been able to hold out much longer under the lash of Nazism and Romanian anti-Semitism.

No Fairy-Tale Ending in Liberation

Their troubles were far from over after liberation. “When we went back to Czernowitz and discovered there was no one left, no one to help us or to rejoice at our return, it was a very difficult time. We lost many things in the war. Most of all we lost who we were. We had been treated like animals.”

Her mother had kept alive the hope of reuniting with husband. But he never came back and was presumed killed. So she and her two young daughters lived in a displaced persons’ camp in the American Zone of Occupation in West Germany for seven years before emigrating to the United States in 1951.

Paula yearned to blend in as an American and cast off the cobwebs of her past. She quickly learned English and applied herself at school. Her mother maintained a strong sense of Jewish identity for them all. Paula worked as a junior counselor one summer at a day camp in Pleasantville, N.Y., run by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. She met a senior counselor named Bill Gris who was a rabbi’s son and her future husband.

“The real reason I married him was I loved the smell of his family’s home,” she says jokingly. “It was clean in a way we immigrants never managed to get. The food was delicious; his bubbie did all the cooking. His bubbie loved me, so she heaped plates high for me.

After Bill finished Army duty, his and Paula’s suitcases would come to rest in Atlanta when he took a job there. Meanwhile, Sylvia would become a wife, mother, photographer and artist who now lives in upstate New York.

Paula began reclaiming her prewar memories at the first World Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors in Jerusalem in 1981.

“That was the most incredible homecoming for all of us survivors. All of us had the same feeling: that God had put his Hand in the fire and had pulled out seeds to reseed the Jewish world.”

She also reclaimed her tears upon hearing “Hatikva,” the national anthem of Israel that promises a future for the Jewish people. Tears also well up when she hears young Jewish children singing songs of hope. A grandmother many times over, Paula appreciates the Jewish people’s optimism and resiliency, building families and contributing to the world after seeing the worst in humanity.

The blue suitcase traveled around the world during her childhood and beyond until it landed in a glass display case at the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta, where Paula is an educator. She and her husband, Bill, have lived in the community 60 years and she continues to tell her story to make a young Romanian girl’s voice heard.

[Published on Aish.com, October 14, 2017]