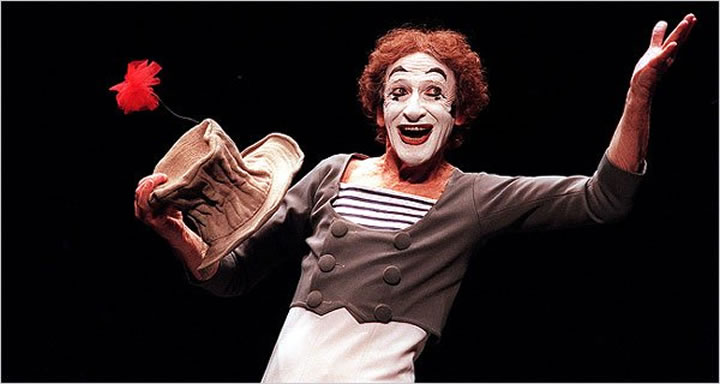

Pantomime artist Marcel Marceau not only entertained with his funny, graceful, exaggerated movements, he saved lives – including hundreds of orphans during the Holocaust.

As a teenager, he put his gift of acting to good use. A member of the resistance movement fighting the Nazi occupation of France, he masqueraded as a Boy Scout director and evacuated a Jewish orphanage. He first convinced the children in eastern France that they were going on a hiking vacation in the Alps. Then he shepherded them to safety in Switzerland. He avoided detection on the perilous journey by charming the children with silent pantomime.

“He was miming for his life,” said documentary filmmaker Phillipe Mora, whose father was Marceau’s partner in the French resistance.

Marceau was born to a Jewish family as Marcel Mangel on March 22, 1923, in Strasbourg on the Rhine. He professionally performed what he called “the art of silence” worldwide for more than 60 years. It all began when he discovered Charlie Chaplin at age 5 and amused friends by imitating the silent-film star.

Marcel changed his last name to Marceau at age 16 to avoid being identified as Jewish. The Nazis had invaded France, and the Jews of Strasbourg, in the Alsace region near the German border, were fleeing to save their lives.

Young Marcel traveled with his older brother to Limoges and joined the underground. Marcel not only mimed to keep orphans quiet as they crossed the border into Switzerland, but he also performed a sleight-of-hand, changing the ages on the identity cards of scores of French youths, both Jews and Gentiles. He wanted to make them seem too young for labor camps or work in German factories for the army.

What I did humbly during the war was only a small part of what happened to heroes who died through their deeds in times of danger.

“I don't like to speak about myself, because what I did humbly during the war was only a small part of what happened to heroes who died through their deeds in times of danger,” Marceau said at the University of Michigan in 2001 when accepting the Raoul Wallenberg Medal in memory of a righteous Gentile who saved thousands of Jews from death in the Holocaust. “Think about the American G.I.s when they were at Normandy and were killed terribly before they reached France.

“We shall never destroy evil, unfortunately. But good exists also among the majority. I will speak only briefly about my own deeds. It is true that I saved children, bringing them to the border in Switzerland. I forged identity cards with my brother when it was very dangerous because you could be arrested if you were in the underground. I also forged papers, not to save only Jews, and children, but to save Gentiles and Jews, especially Gentiles because there was a law in Vichy-occupied France – to send the young French men, who were 18, 19 years old, to factories in Germany to work for the German Army. And then I had an idea to bribe the officials, and make people look much younger in their photos.”

That night in Michigan Marceau gave the crowd advance warning: “Never get a mime talking, because he won’t stop.”

He talked about the acting skills that enabled him to save lives. The cousin who hid him during the war knew Marceau later would make an important contribution to the theater.

He talked about his father, whom he didn’t have a chance to rescue. The elder man, a butcher, died in Auschwitz. “I cried for my father,” said Marceau, “but I also cried for the millions of people who died.”

The great mime hadn’t spoken about his World War II experiences earlier in his life. His silence wasn’t surprising, according to University of Michigan professor emerita Irene Butter, who introduced him as the Wallenberg Medalist.

“Many, if not most, survivors of the Holocaust were not able to speak about it for nearly half a century,” explained Butter, herself a Holocaust survivor. “Marcel Marceau is known as the Master of Silence – it may have been particularly difficult for him to break the silence about this tragic period in his life.”

He built a career on that silence.

In 1944, after Paris was liberated, Marceau enlisted in the French Army, serving side by side with American G.I.s. As he recalled, “We were already at peace in December 1945, but we were still mobilized. I went to Frankfurt where there was the Sixth Army of General Patton, and I met Captain Parker. He said to me, ‘Young man, what will you do later?’ I said, ‘Pantomime…you know, Chaplin, Keaton, I want to make theater without speaking.’”

The captain asked Marceau to demonstrate. He obliged with shticks about walking against the wind, climbing stairs and engaging in a tug of war. Then Parker asked him to entertain the U.S. troops – 3,000 strong.

With white face, arched eyebrows and red lips, Marceau continued to communicate to audiences through movement for decades.

Until his death on Yom Kippur at age 84, Marceau performed 300 times a year and taught at his pantomime school in Paris. He would have been 93 this month. The artist who brought poetry to silence was laid to rest in a Paris cemetery in 2007.

[Published on Aish.com, March 20, 2016]