“Are you Jewish?” the German officer asked Private Simon Langer. They were in Estonia, during World War I.

“Yes,” the young soldier admitted in German.

“Me too,” came the unexpected reply. Then, another surprise: “I am Officer Lipkovitz, and from now on you’ll no longer be in the trenches with the other soldiers. You’ll be my orderly, and you’ll help me fulfill my duties as an officer. You’ll follow my orders and live in the officers’ bunk with me, and do what I tell you needs to be done.”

I can only imagine how happy my father must have been when he heard this pronouncement. He no longer had to endure the cold in the trenches; he would live comfortably in the heated officers’ barrack.

Hans Lipkovitz probably saved my father’s life. And by a remarkable coincidence, my family was able to help elevate Officer Lipkovitz’s soul 75 years later.

It all began when my father, Private Langer, was born in 1897 in Alsace Lorraine, France. Because of politics the official language was at times French, at times German. But the inhabitants had their own dialect, a mixture of both languages. Alsace was part of France until the end of the Franco-German War in 1871, when it was annexed to the German Empire. Still, the population retained its allegiance and loyalty primarily to France.

When World War I broke out between France and Germany in 1914, Germany drafted Private Langer and other young Alsacian young men into its army. The Germans realized these soldiers would not fight their countrymen in France, so sent them east to battle the Russians.

From One Jew to Another

Private Langer and his fellow soldiers were stationed in Tallinn, Estonia. They never saw battle but died by the thousands because of the extreme cold. As a religious Jew, my father would rise early in the morning and wrap himself in tallis and tefillin to pray. That’s how Officer Lipkovitz picked him out as a Jew among the French soldiers.

Not long after, Officer Lipkovitz asked him, “Would you like to visit your mother? Go to Alsace and buy me a box of cigars.” He gave Private Langer money for cigars and train fare to Alsace.

Did he expect my father to return to Estonia? We don’t know. But Private Langer, an honest and reliable young man, did go back after visiting his mother in Alsace and gave Officer Lipkovitz the cigars he had purchased for him.

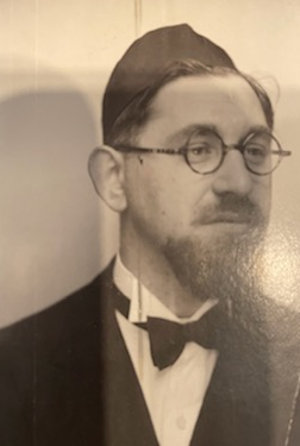

When World War I ended in 1918, soldiers who were fortunate enough to have survived went home to put their lives back together. My father decided to become a rabbi and enrolled in the Hildesheimer Seminary in Berlin. After his ordination, he married my mother, Caroline Schweizer, in Strasbourg in 1925. They had met during the war when my mother’s family provided kosher food to my father and other soldiers stationed in Germany.

By the 1930s my father had become a prominent rabbi in Paris. Before the outbreak of World War II, he parlayed his fluency in French and German language and culture into important rabbinic missions to benefit the Jews of Western Europe.

An Officer and a Gentleman

That’s how he happened to find Officer Lipkovitz again. Upon arriving in Brussels in 1938, my father walked outside the train station looking for a taxi. Whom did he see but Officer Lipkovitz, playing violin in the square nearby. The former Private Langer ran with outstretched arms and shouted, “Lipkovitz, Lipkovitz!” The former German officer responded, “Langer, Langer!”

They hugged and began to catch up on the many years since their last encounter. My father asked, “How did you get to Brussels, and how do you earn a living?” Lipkovitz responded, “Even though I was a German officer during the war, the Germans expelled me and many other Jewish officers. Since I had an elderly aunt here, I decided to come to Brussels. Here I stand and play the violin to earn a few francs.”

Recalling how the shabbily dressed person before him had saved his life, my father implored, “Officer, what can I do for you? How can I repay you?” Lipkovitz had a simple answer: “My violin is old and doesn’t sound the way it should. I wish I had a new violin so that I could play beautiful music to earn a few francs from passers-by.”

My father quickly reached into his pocket and gave Lipkovitz the money for a new violin. Then the former officer and soldier parted company. But their story didn’t end there.

Fleeing to Safety in an Army Convoy

In 1939 France and Britain declared war on Germany, which had invaded Poland. My father served as a chaplain in the French army. That turned out to be a blessing when France surrendered and was divided into two zones. My family was able to flee in an army convoy from Nazi-occupied Paris to Marseille in the south.

Alice Weiss

As chief of the Jewish community in Marseille, my father visited a large internment camp west of the city that accommodated Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis. One day as he was distributing food in the barracks he saw Lipkovitz in one of the beds, suffering from gangrene.

He ensured that his former officer received the medicine and food needed to manage deteriorating health. On one of his last visits, my father looked for his friend in the barracks, but Lipkovitz was nowhere to be found.

My father never learned of his officer’s fate.

In the Nick of Time

In 1941, due to my mother’s urgent insistence, my father packed up our family to escape by boat from Marseille to America. Within a week after our departure, the Germans came for my father because he was head of the Marseille Jewish community—but they were too late.

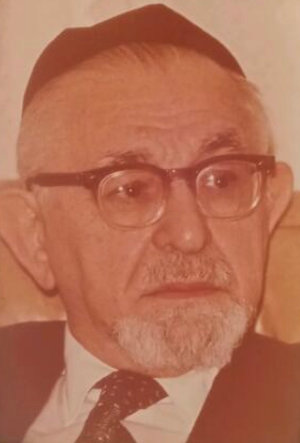

A father of four, he became a beloved rabbi in New York, with dozens of grandchildren and great-grandchildren across America and Israel. Years after my father died in 1987 at age 90, my niece discovered information about Lipkovitz’s fate. According to her research at Yad Vashem, Lipkovitz died in 1941 near the city of Gurs by the internment camp where my father had last seen him.

Exactly 75 years after the Hebrew date of Lipkovitz’s death, my brother took on the merit of going to synagogue to say kaddish (the mourner’s prayer) for the officer. He asked me to light a yahrzeit memorial candle for someone very special whom we had never met. Thus, we were able to pay tribute to the man who saved my father’s life and ensured the continuity of future generations.

As told by Denise Heimowitz

[Published on Aish.com, June 6, 2021]