Can a rabid white supremacist, neo-Nazi, Ku Klux Klan leader change? TM Garret, a German-American who used to fit all those labels, says yes.

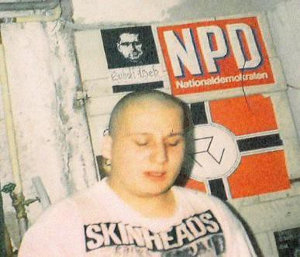

As a young man he sported skinhead tattoos. As a 44-year-old grandfather, he is a champion of peace and human rights who sometimes wears a yarmulke when visiting synagogues.

He wore one recently when relating his compelling story of transformation to a packed house at Chabad’s Intown Jewish Academy in Atlanta. Garret speaks at synagogues, mosques, churches, colleges, schools and sheriff’s departments across the United States to help people understand the roots of hate and how to respond to it. In Garret’s case, telling Holocaust jokes with his peers at age 13 provided a sense of belonging for the first time in his life. Today he differentiates between intentional and unintentional anti-Semitism, asserting that his slurs fell into the latter category.

Bigotry: A Way to Blend in

With a tangle of childhood wounds, he acted out to get attention and fit in. “I was not born in a hateful environment,” says Garret, enumerating many factors that made him feel like an outcast in the small German town of his youth. Both parents had a drinking problem, and they divorced shortly after his birth. They were Catholics among 500 primarily Protestant neighbors. His mother was rearing four children by herself, which was unusual in those days.

“My mom was just so busy fighting her demons, I just thought she didn’t care. Emotional support was missing.” Garret’s older sister took care of him. Meanwhile, his absentee father died when he was 8.

“I was the weird kid, weird family, no hobbies, single mother. I was a perfect victim for bullies. That’s what happened. I was bullied in school.”

His star rose when he and his classmates started learning about the Holocaust and World War II in school. They began telling each other Holocaust jokes. Like the older boys, Garret would also pepper his rants with anti-Semitic and Hitler jokes. The latter were politically incorrect, if not downright egregious. Yet Garret continued because of the payoffs he received.

“The bullying stopped because nobody wanted to pick a fight with a Nazi." He recalls. "They put me in a box; I was known as the Nazi kid from then on. Before I was just nobody. It gave me an identity, even though I didn’t like it.”

His persona grew more fearsome when he joined the Nazi party at age 17, then found a vehicle to carry his hate messages wider as a neo-Nazi singer/songwriter at age 19. People were listening to him. He felt like a real somebody.

In the late 1990s, his anti-Semitism had morphed from unintentional to intentional, thanks to propaganda about Jews he found on the Internet. By age 23, he was a full-fledged white supremacist and a Ku Klux Klan leader in Europe.

Meanwhile, Garret suffered greatly from paranoia. He feared police kicking in the door and taking him to prison because of Germany’s strict anti-hate laws. He feared that the groups he hated, including Jews, would take over the world.

“I thought if I go to prison I’m no good for my children. There was tension in the family. Because of all that, I resigned from the groups although I was still a racist.”

He began questioning his life and in 2002 plucked up the courage to move his family to another town 100 miles away. He decided to leave behind 15 years of ideology and the support network associated with it.

Kindness: An Unexpected Twist

They rented an apartment tucked in a house owned by a Turkish Muslim, which didn’t sit well with Garret. “I looked at my wife and said do we really want to do that. But I was desperate.” Little did he know this was a turning point.

The Muslim landlord, who lived downstairs, kept having computer problems and offering Garret work to fix them. He always proffered hospitality, with Turkish tea and cakes. After six months, the man invited Garret to join his family for dinner.

“He showed me compassion. All that hate I had, it felt like it lay in front of me in crumbs. I had to decide either to take those crumbs and put them back into a loaf of hate or analyze the situation.”

Garret began making radical life changes. He started learning about the groups he had hated, beginning with Muslims in Germany.

In 2012 he realized a childhood dream of moving to America. After settling in the Memphis area because of business connections there, he began getting to know African-Americans and Jews and laying the foundation for his future interfaith work.

Born as Achim Schmid, the German-American human rights activist founded C.H.A.N.G.E, which stands for Care, Hope, Awareness, Need, Give and Education. The nonprofit group spearheads community outreach programs, food drives, seminars, and antiracism and antiviolence campaigns.

Garret also helps people transition out of extremist organizations and remove racist and hate tattoos – as he did. He is the founder and organizer of the annual Memphis Peace Conference and a campus speaker against anti-Semitism for the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

Compassion: The Key to Connection

“You could say my business is compassion. There was a time in my life when there was no compassion,” he observes. “On one hand I would love to go back and change my life. On the other, I wouldn’t have the experience to do what I do now.”

He suggests people seek compassion for those they disagree with, whether religiously, culturally or politically. Try to understand them as people, even when it is difficult, rather than casting them aside as a label. Look for ways to have a conversation. Seek common ground.

He suggests people seek compassion for those they disagree with, whether religiously, culturally or politically. Try to understand them as people, even when it is difficult, rather than casting them aside as a label. Look for ways to have a conversation. Seek common ground.

When it comes to hate incidents, legal punishment and boundaries are important, he emphasizes. If you see hate on social media don’t get involved in a conversation. Report the post to Facebook or use an app like CombatHate by the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

[Published on Aish.com, January 20, 2020]